Are you paying attention? We are paying attention . . .

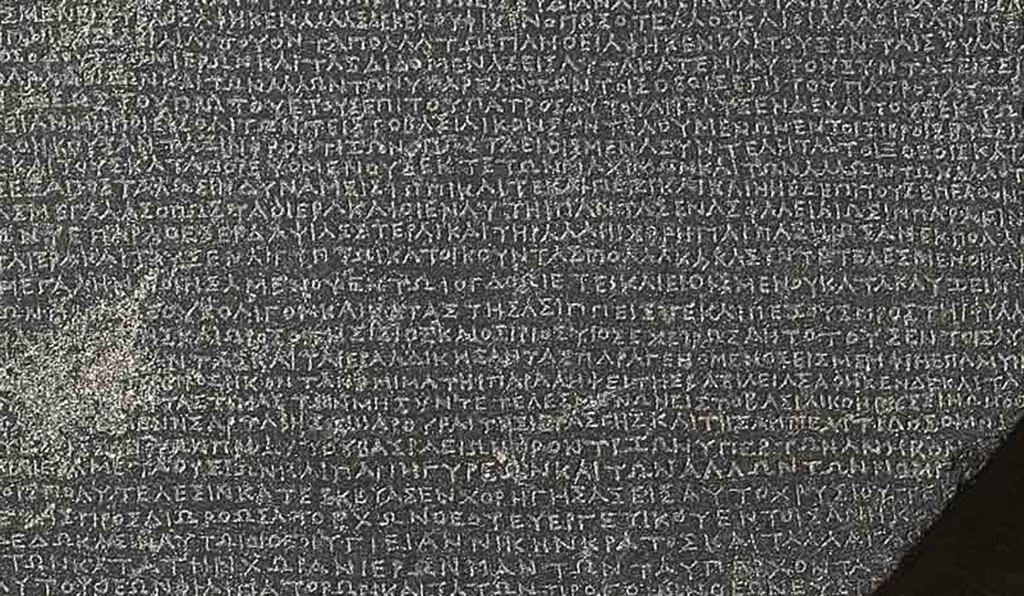

In the British Museum in the 80’s, the Rosetta Stone was not (at least in my memory) encased in glass but sat open to the air. As I stood beside it and imagined touching its incisions, another tourist, part of a small group identified by matching bags, began filming the stone with a video camera. At this time, before smart phones and digital cameras, I rarely saw anyone using a video camera in public.

The stone was motionless. It did not vibrate. The stone was silent. It did not hum. The air was still. No dust stirred. The afternoon light was even and unchanging.

The rest of the group was talking quietly, their comments echoing what I was thinking but not saying aloud (“Look, it’s the Rosetta Stone! It’s old! It’s the key! It’s It’s smaller—larger—different—just as I imagined.”)

The tourist filmed for as long as I stood there and was still filming when I left. He did not zoom or pan or change his point of view. I was perplexed. What would a video capture that a still photo would not? The lens was fixed and focused intently. It was focused longer than I was. What did it see? What did he see?

Later, when I met my daughters in the museum cafeteria, I predicted that when their father joined us his first words would be “So, tell me. Did you see the Rosetta Stone? Was it interesting?” He asked. They did. It was.

I don’t know if I saw the Rosetta Stone. I saw the tourist. I saw my perplexity. I saw my feeling of superiority, as I compared my direct experience with his mechanical one. But in actuality I was just as distracted and just as distanced as he, as nothing in my viewing of the Rosetta Stone changed my already formulated response. I had not actually had an encounter with the Rosetta Stone, although I had had an encounter with the tourist.

On my first mapping trip across Nebraska I stopped at Red Cloud and then drove south to see the Republican River and to set the boundary with Kansas. I pulled off at the Willa Cather Memorial Prairie just before the state line.

The Cather Prairie isn’t just a prairie; it’s a memorial prairie and I was expecting something “memorable.” I photographed, but did not read, the state Historical Marker, which is situated in front of a limestone bench, another kind of memorial, from which, presumably, one could contemplate the memorial of the prairie.

I set up my video camera to film the prairie and then began taking still shots, frustrated by the signs of human occupation: fences, cattle, distant houses, distant highways. I tried, but failed, to frame my shots of the prairie to edit out everything that was not grass or sky, to capture my idea of “prairie.”

While I was shooting photos two other observers sat down on the limestone bench. When I looked, later, at the video, I saw that the camera, looking at the prairie, had captured them, also looking at the prairie. (Only one of them was looking directly at the prairie. The other had her camera looking at the prairie and she was looking at the camera’s LCD screen. So my camera captured her looking at her camera looking at the prairie.)

I did not, at the time, recall the Rosetta Stone tourist.

To me, the prairie looked too ordinary. It didn’t look preserved, or endangered or any way special. Without the marker I would have just dismissed it as “fields.” But I did begin to understand that what I was intending to do, traveling across Nebraska, was not as straightforward as I’d imagined.

I intended to find out for myself what it was like to stand on the ground in a particular spot. I intended to understand a location as more than coordinates on a map. I intended to travel. Then, to stop. Then, I hoped, I would see, hear and feel. I intended—I expected—to have some sort of experience.

But at the Cather Prairie, all I had done was document, and I had done that in the most cursory way. The only interesting thing about my documentation was that I had, by accident, captured someone else also documenting.

I had sensed very little, understood even less, and experienced only the wry recognition that like the other two visitors, I was looking at something that couldn’t really be seen, at least not from this fixed and controlled viewpoint.

Would I ever sense? I wondered. And not just “note” or “capture” or “archive.”

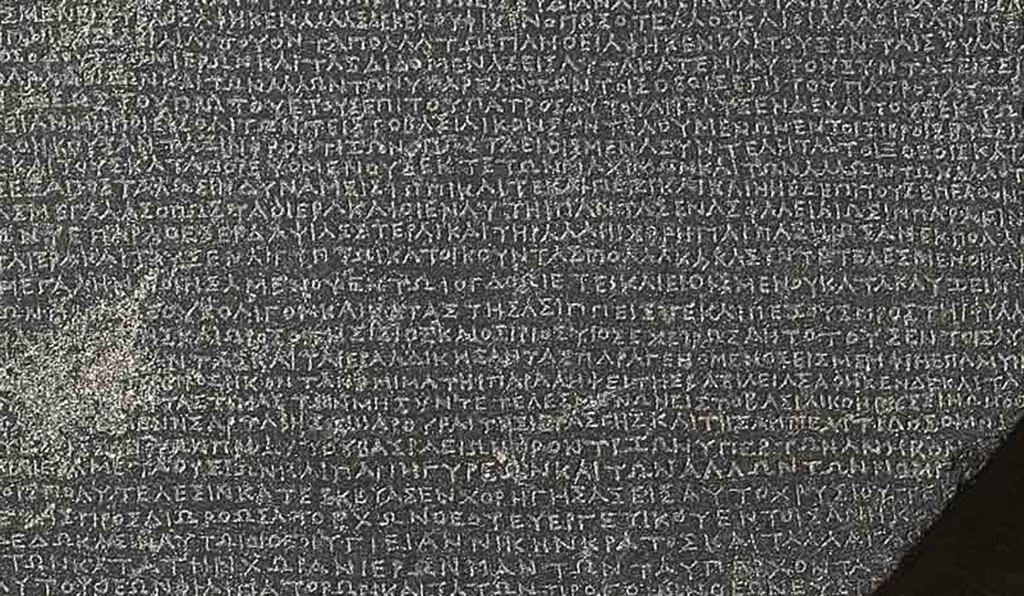

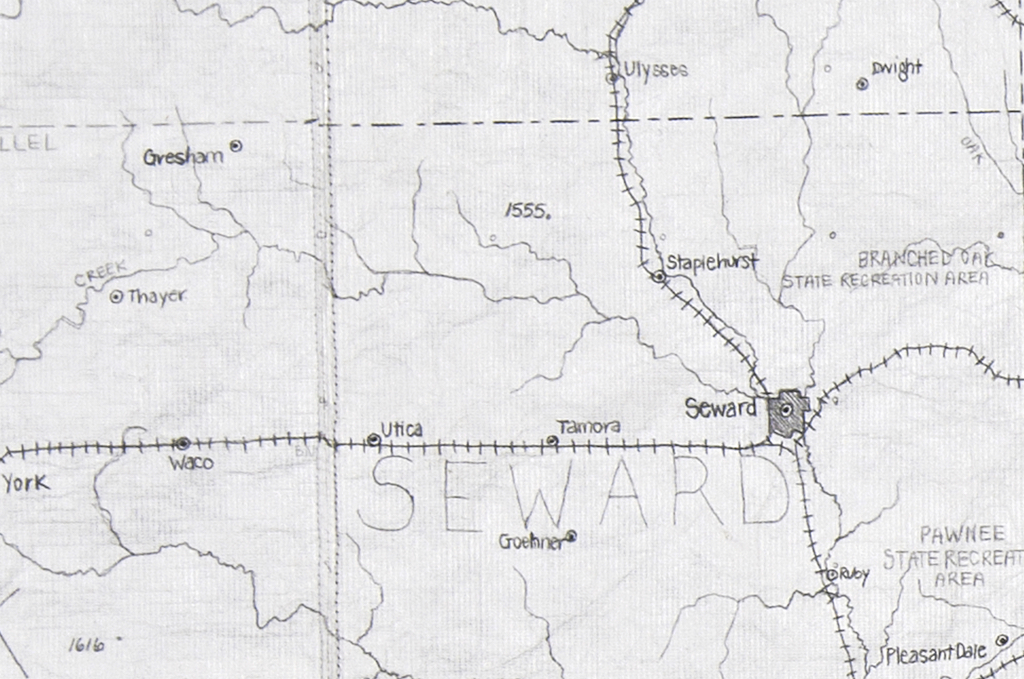

The next year, on another mapping trip, I drove into Seward, Nebraska for the first time. It was the end of September, not summer and not fall. Just before reaching the center of town I drove over the Big Blue River and then turned off into a city park to photograph it. The park seemed familiar: green lawns, barbecue grills, well-tended driveways.

I parked my car to walk to the river which was narrow and flowing with water. The river was muddy and the trees were still green and the light was hazy and soft.

There was nothing special about this location. It wasn’t scenery. It certainly wasn’t a “vista.” And yet, standing there, watching the water, seeing its movement, hearing it flow, smelling the leaves and feeling the moist earth sink under my feet as I stood on the river’s banks, I realized that there was more going on at this location than I could ever, ever, ever capture, no matter what media I tried to use.

Here is what I had drawn:

And this is what I saw:

And both, the photograph, and the map, are inadequate to describe what I felt standing there.

I regard the tourist and the observers differently now. Not as objects of wry disdain but as markers, beings who who by their actions suggest: “Perhaps you should also look at what I am choosing to archive.”

I realize now I can’t predict my experience. I can’t assume I’ll have any experience, and if I do, I can’t adequately archive it. I can’t download it or upload it or preserve it. The sensory information of any moment—the sounds, the textures, and my perception of space and light and air—is beyond the capacity of any recording device, even—especially—my memory.

I had an experience at the Big Blue River, an experience I can’t transmit but can acknowledge.

Like the tourist, like the observers, my looking is a signpost, an invitation for your looking. I can value what I found there. I can point it out to others, and to you. I can use it to make something else visible.

That is, I can engage in the task of the artist:

This work of the artist, to seek to discern something different under material, experience, words, is exactly the reverse of the process [of] every minute that we live with our attention diverted.

—Marcel Proust

We are in danger.

We have forgotten

the birth of air, the birth of water.

We are attending

the death of hope.

Are you paying attention?

We are paying attention.

We are paying attention

to purchase regret.

—Elizabeth Ingraham, “danger”