Mapping Nebraska

The traveler who has lost his way doesn’t want to know where he is. What he wants to know is “where are the others?”— Alfred North Whitehead

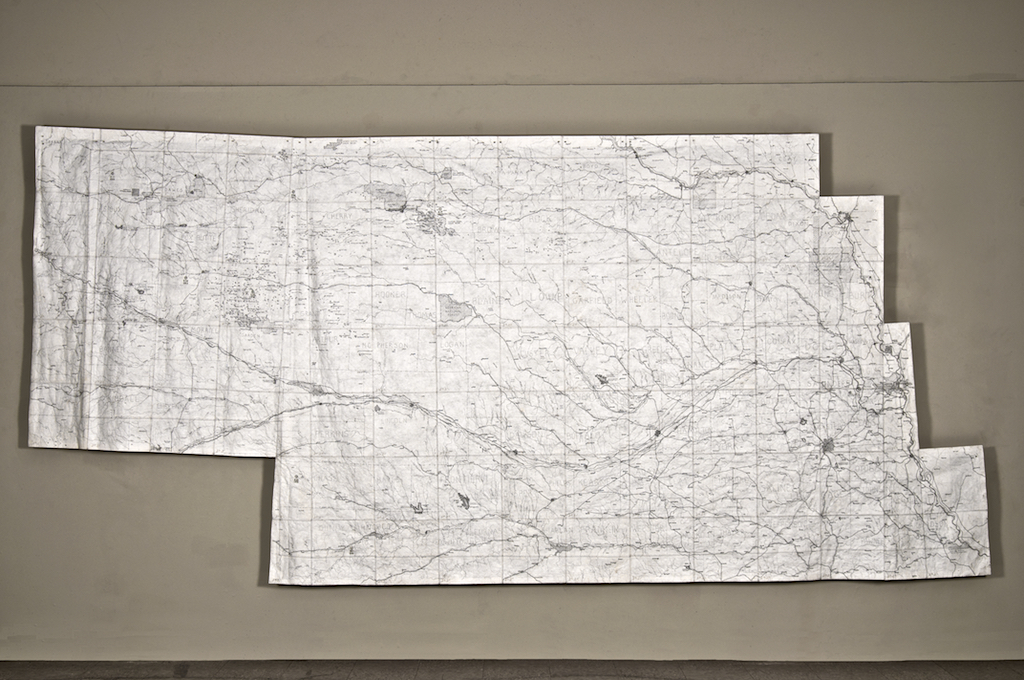

I’m mapping Nebraska: making a stitched, drawn and digitally imaged cartography of the state where I live. Locating myself. And the viewer. Trying to understand the place where I am.

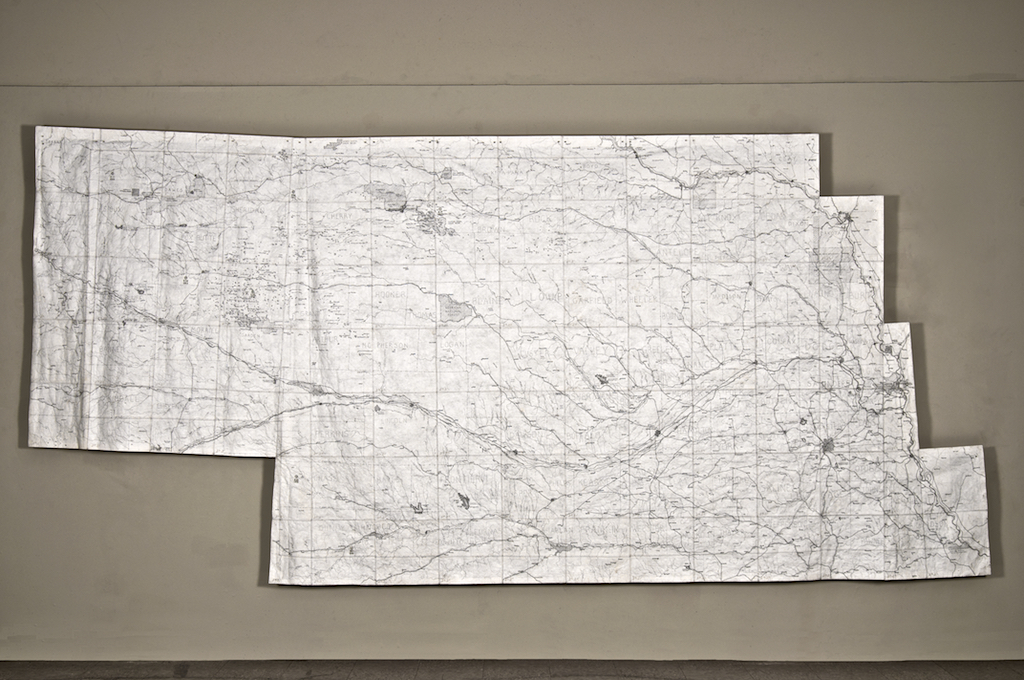

I began by drawing all of Nebraska—95 squares stitched together to form a 15-foot Locator Map. My map records physical features—lakes and rivers creeks—and geographical features —railroads, parks and towns—and all are to scale (1″ = 2.75 miles) and in their correct relative position. It’s as accurate as I can make it.

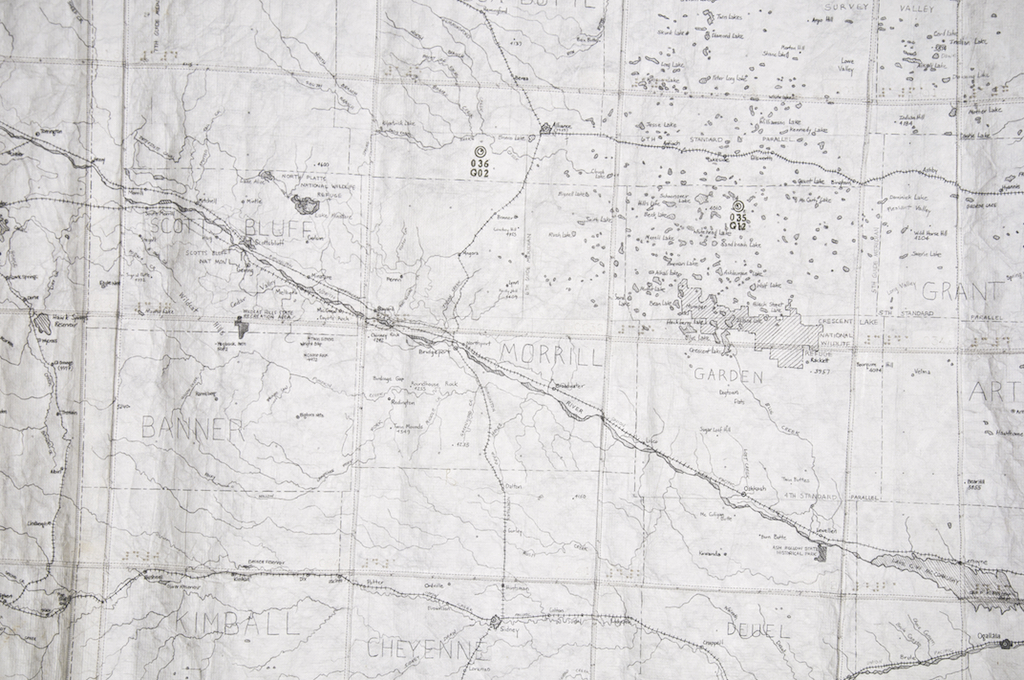

I created this map of Nebraska for some of the same reasons we’ve long used maps—to see where I am relative to the other places, to get a sense of my surroundings and to try to comprehend a whole I can not see. The Locator Map tells me about borders and boundaries—county lines and standard parallels and the extent of the Nebraska National Forest and how far, in relative terms, Antioch is from Ellsworth. It gives me a geographical overview. It lets me know, if I’m drawing the area around Gaunt Lake, that I’m north of Oskosh and East of Alliance, in Sheridan county.

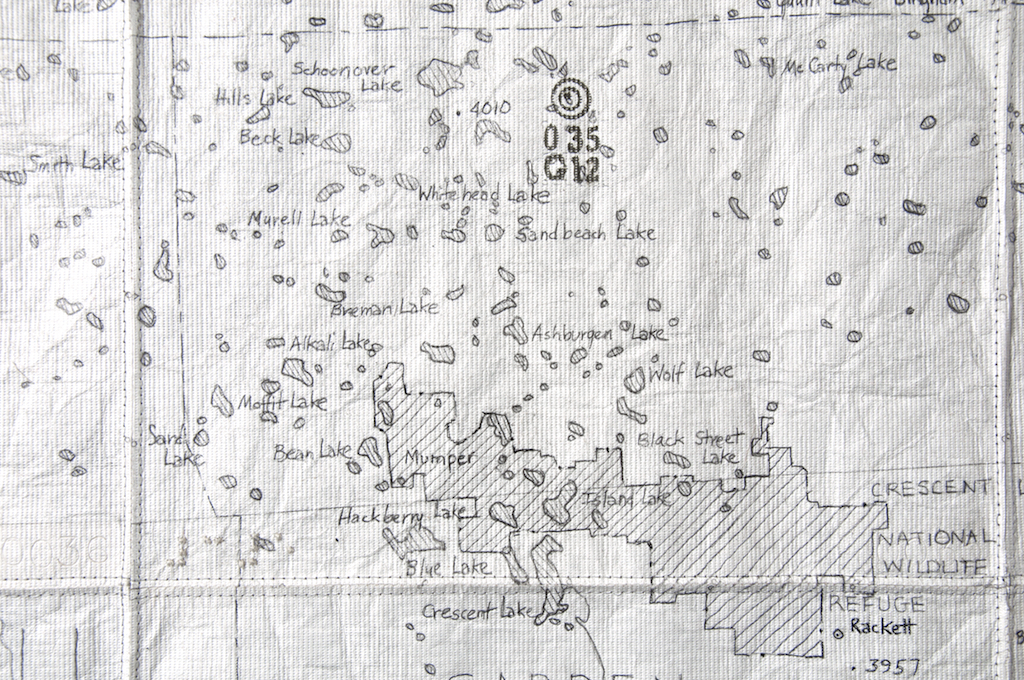

I remember drawing Section 35, out in the western part of the state, with no rivers and no creeks but dotted with lakes like holes in a sponge. What could this terrain look like? I wondered.

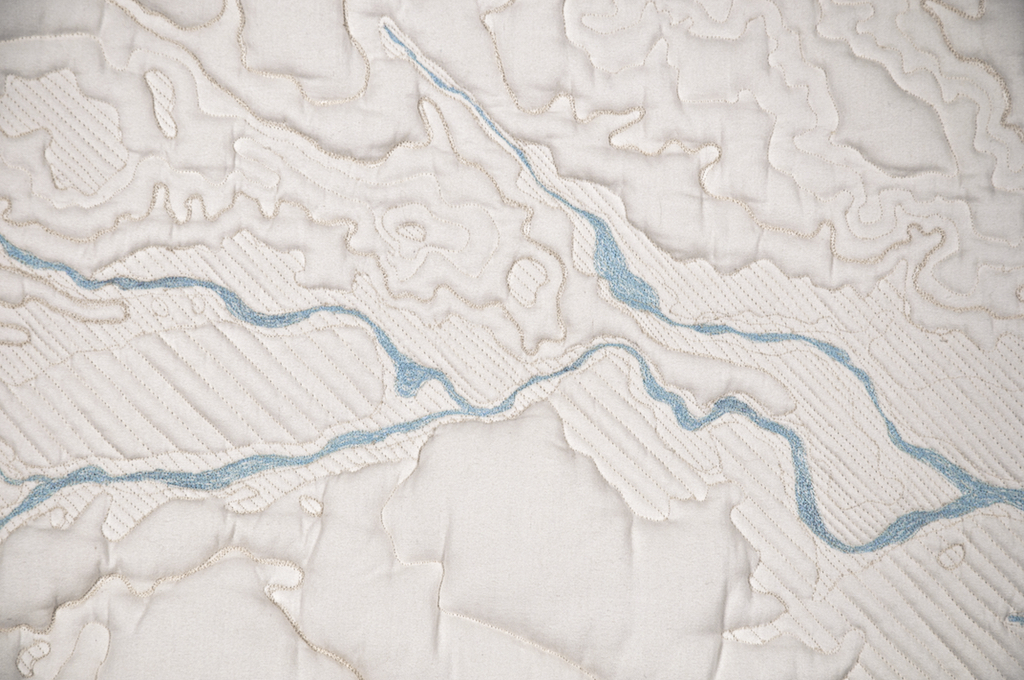

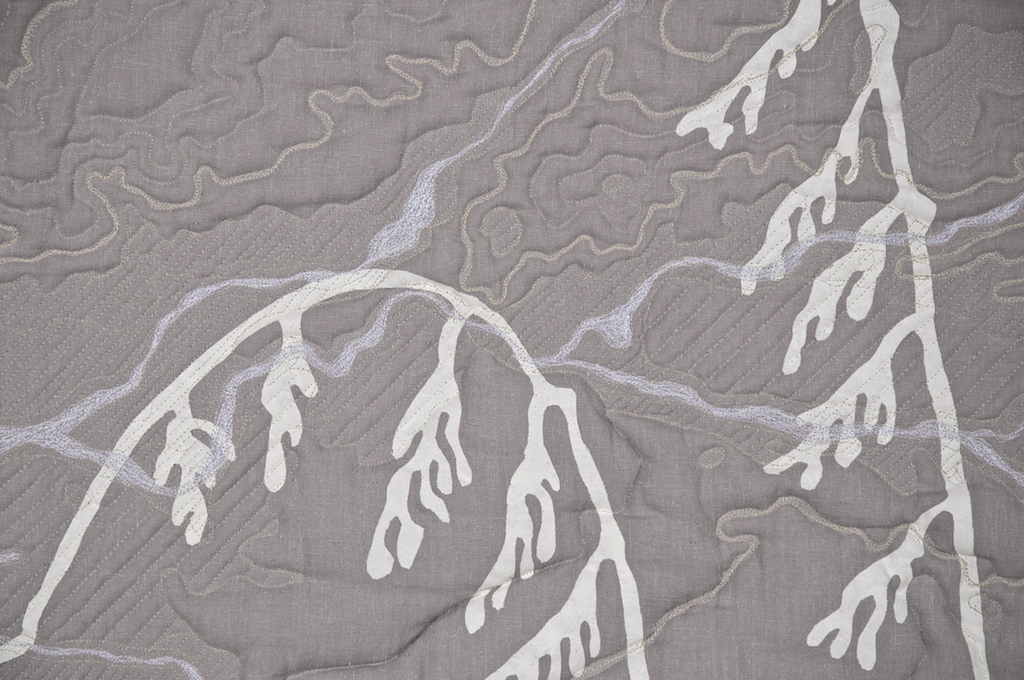

It is this topographic terrain I try to express in 24” quilted squares. I select an area, in this case section 35, using software to view it at a larger scale so that the physical topography is expressed as contour lines and rivers and lakes are clearly visible, and then stitching that terrain.

But I had to drive to Crescent Lake, on a gravel road that became a dirt road to understand the terrain. I needed to take myself up and over this terrain in order to stitch it. This action of traveling up and down and over and around the actual terrain informs my stitching.

I’m translating the topographic terrain as stitched relief, using the same vocabulary I use when drawing: a meandering lines and eccentric hatching and a sort of scumbling—decorative, but not too decorative—for the lakes. When I stitch the water I imagine the actions of the wind the effects of its currents.

The blue of the water appears white on the reverse. These ghost lakes and ghost rivers combine with the stenciled grasses and with the stitched lines in unexpected and unpredictable ways.

My stitched lines meander, losing course and then regaining it. They carve through the height of the quilted stuffing, containing and bounding it. Lakes and their surrounding land are subdued through hatching. Sections fasten together with a system of buttons and tabs which echo the grid markings of my drawn Locator Map.

Like all translations, something is lost as well as gained. Completeness and accuracy are beyond my capabilities. But I can aim for fidelity, for truthfulness. I can make visible and palpable the difference between how boundaries and contours look on the map and how it feels to journey over and through gentle hills.